Key Takeaways

- Not all AI tools are equal. Large, general-purpose models use far more energy and water than smaller or specialized tools built for specific tasks.

- Image and video generation carry a much higher footprint. AI-generated visuals, especially video, can consume orders of magnitude more energy than text-based queries.

- Efficiency gains aren’t guaranteed. Newer or more advanced AI models are not always more efficient. Higher performance often comes with higher resource use.

- AI infrastructure affects real communities. Data centres place significant strain on electricity grids and freshwater supplies, with disproportionate impacts on nearby populations.

- Intentional use makes a difference. Choosing the right tool, avoiding unnecessary AI use, and opting for smaller or local models can significantly reduce environmental impact.

Responsible AI Use at a Glance

- Choose the right tool: Use specialized tools (e.g., Grammarly for writing, Semantic Scholar for research) instead of large general-purpose models.

- Think smaller: When you need an LLM, opt for lightweight or local models like SmolLM WebGPU.

- Don’t default to AI: If a web search or traditional tool works, AI may be unnecessary.

- Use AI to support expertise: AI works best when it enhances existing knowledge.

- Watch for passive AI use: Many search engines enable AI by default. Turn it off or switch to classic search options.

AI: The Elephant in the Room with a Big Footprint

Understanding AI

Energy Use

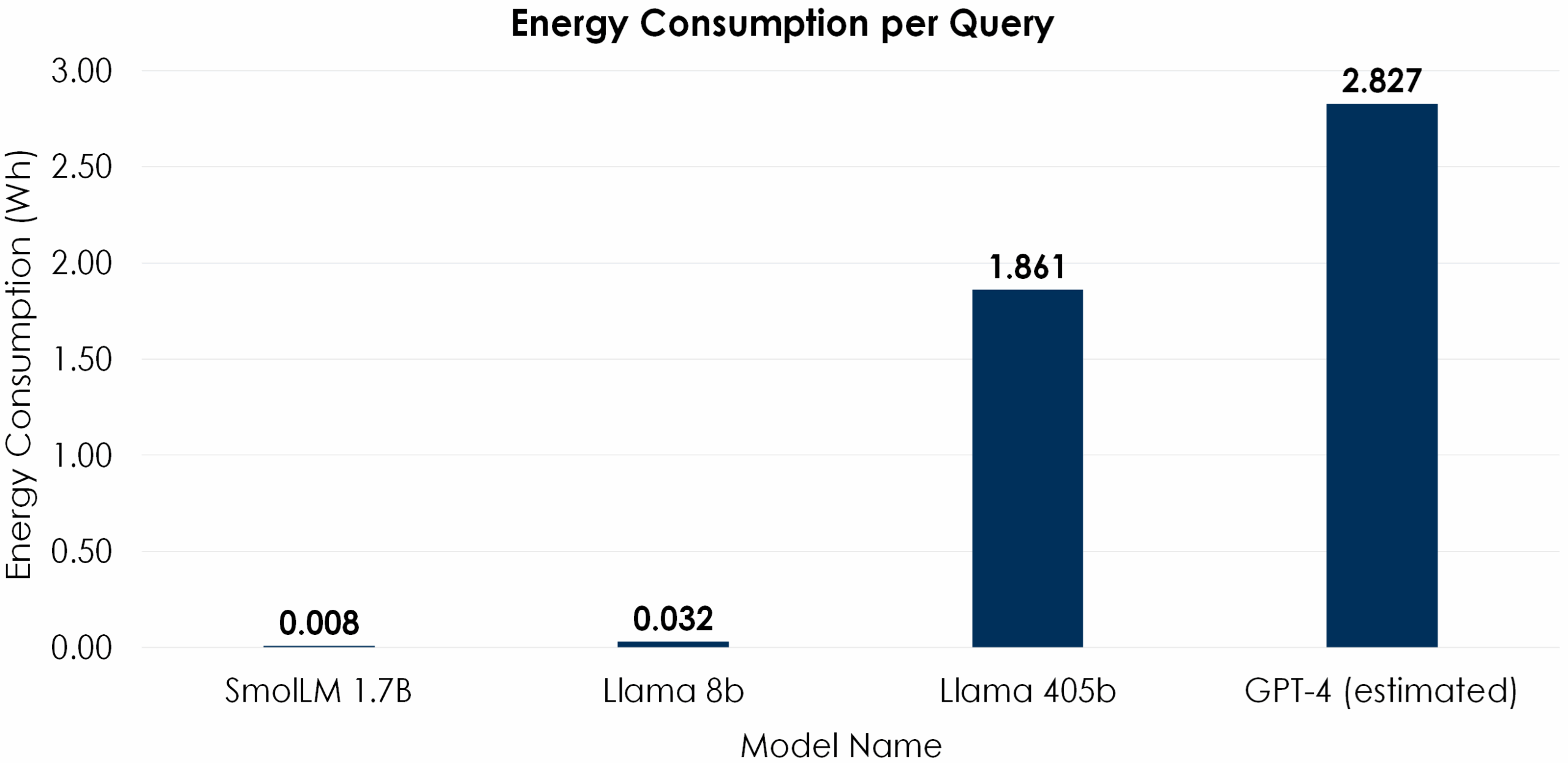

So, what do the numbers mean? The values in the graph are given in watt-hours (Wh), a unit of energy equal to one watt of power expended over one hour. A typical modern LED light bulb is rated at 6 watts, so leaving it on for one hour would consume 6 Wh of energy. Your electricity provider likely bills you per kilowatt-hour (kWh); one kWh is equivalent to one thousand Wh.

So, what do the numbers mean? The values in the graph are given in watt-hours (Wh), a unit of energy equal to one watt of power expended over one hour. A typical modern LED light bulb is rated at 6 watts, so leaving it on for one hour would consume 6 Wh of energy. Your electricity provider likely bills you per kilowatt-hour (kWh); one kWh is equivalent to one thousand Wh.

Water Use

The Emissions of AI

Social Implications of Energy and Water Consumption

Future Potential for Model Collapse

So What Does This Mean?

What Can We Do?

- Choose the right tool for the job. Large program models like ChatGPT use more parameters to have a wide variety of questions they can answer, but that means more energy use. Using specialized models is just as accurate but uses fewer parameters to answer specific queries, resulting in less energy use. This means if you’re writing code, use an AI code writing assistant that has been trained on code. If you need help with grammar, try Grammarly. Some specialized models we recommend are:

- For writing: Grammarly: Free AI Writing Assistance – built on Grammarly’s wealth of experience in helping people write better

- For research: Semantic Scholar | AI-Powered Research Tool – uses a model developed in-house to search for relevant research papers contextually

- General questions: SmolLM WebGPU

- Start with what you already know. AI is most effective when it’s used to bolster existing expertise. An expert knows when something should be done with “old tech” versus when AI adds meaningful value and has the insight to understand if AI results are valid or not.

- Think critically. If you find yourself defaulting to using AI, step back and think, “How would I have done this before ChatGPT existed?” If a web search is just as effective, avoid using AI. You don’t need Chat-GPT to tell you how to boil an egg.

- Think small. If you need an LLM, look for a model with a small number of parameters. A favourite of ours is SmolLM WebGPU which, once loaded, can run locally in your browser, skipping the data centre altogether, reducing energy and water use.

- Switch search engines. Most search engines have now fully integrated AI into their results, meaning you are using AI without trying to. However, there are some browsers that either don’t have it at all or have an option to turn it off. Go to your browser settings and switch off automatic AI answers, or switch browsers. Our favourite for a more classic search engine experience is Dogpile.com

Conclusion

As AI becomes more embedded in our daily lives, it’s crucial to recognize the energy footprint behind the technology. Choosing models wisely, resisting the urge to treat AI like a search engine, and advocating for sustainable practices such as renewable energy and innovative cooling methods are all steps we can take to reduce its impact. Most importantly, the conversation doesn’t end here. AI is a rapidly evolving topic, and by sharing what we learn, we can inspire others to think critically, act responsibly, and push for a future where innovation and sustainability go hand in hand.